Favourite Games

New Games

Conway’s Game of Life

Some games need no players. Some simulations don’t simulate anything in particular — and yet, they ripple with movement, tension, and meaning. Conway’s Game of Life is one such entity. Neither puzzle nor story, it exists in a category of its own: a silent performance of rules, run in grids of black and white, unfolding without direction and yet never quite random.

This is not about shooting aliens or collecting coins. This is about existence on a binary scale — life or death, pixel by pixel.

The Quiet Mechanics of Motion

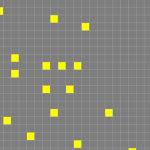

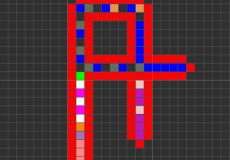

On the surface, Conway’s Game of Life is a grid. Each square (or cell) is either “alive” (on) or “dead” (off). You begin with a pattern: maybe a few living cells scattered like seeds. Then, you press play.

That’s it. You watch.

Behind the scenes, the rules are as follows:

- If a living cell has 2 or 3 living neighbors, it stays alive.

- If a dead cell has exactly 3 living neighbors, it is reborn.

- Otherwise, cells die or stay dead from loneliness or overcrowding.

Nothing flashy. No RNG. Just cold logic. But when these rules cycle again and again, strange things begin to happen.

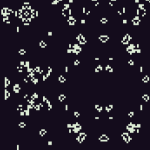

Behavior Without Will

A single glider drifts across the grid like it knows where it’s going. A block forms and refuses to change — perfectly stable. A chaotic mess transforms, settles, flickers… and stops.

This is emergent behavior: patterns that act like they’re “doing something,” even though they have no knowledge, no agency, no memory. They’re just collections of cells, reacting blindly to local conditions. And yet they move, replicate, communicate.

One of the strangest things about Conway’s Game of Life is how quickly people start to anthropomorphize it. That shape is “running away.” That formation is “attacking.” You can’t help it — the patterns look alive.

Notable Organisms on the Grid

Over the years, explorers of the Life universe have cataloged thousands of known patterns. Here are a few of the most iconic:

- Glider: A five-cell shape that moves diagonally forever. It’s often the first moving object new players discover.

- Beacon: A pulsing four-block pattern that loops every two steps.

- Pentadecathlon: A long, narrow shape that flickers in place with a period of 15.

- Gosper Glider Gun: The first known pattern that produces an endless stream of gliders — something like a factory in a pixel world.

Each of these isn’t just a design. It’s a behavior — a rhythm, a result of the rules looping endlessly through themselves.

Beyond Entertainment: A Computational Giant

It might surprise you to learn that Conway’s Game of Life is Turing complete. That means it can — in theory — do anything a computer can do. You could, with enough patience and space, simulate a calculator. Or a physics engine. Or even an entire operating system… all through gliders, switches, and bouncing patterns of light and dark.

That’s not just a mathematical curiosity. It’s a humbling reminder: complexity doesn’t require complexity. Intelligence, functionality, recursion — all these can arise from stunningly simple conditions.

No graphics cards. No code. Just logic, repeating.

The Philosophy Hiding in the Grid

It’s tempting to call Life a model for biological evolution, or a metaphor for consciousness. Some do. But it resists clean comparisons.

It is not a simulation of life — it’s a stage where the idea of life emerges accidentally.

And it raises fascinating questions:

- What is the minimum required for something to look alive?

- If patterns can replicate, interact, or evolve without design, what does that say about design itself?

- Can something have function without purpose?

Watching a Game of Life simulation long enough can make you start wondering about more than just pixels.

People Who Watch the Grid

There’s a whole underground world of people who obsess over Conway’s Game of Life. They build constructs — complex arrangements that do very specific things. Some build glider-based computers. Others try to find breeders (patterns that grow over time). Some chase the ultimate pattern: infinite growth from a simple start.

They speak in strange terms: “puffer trains”, “wickstretchers”, “slmake syntheses”. They use tools like Golly, an open-source simulator, and share findings in online databases like Catagolue — a sprawling archive of known Life phenomena.

This is not just hobbyism. It’s more like collaborative archaeology in a universe that only runs forward.

Why It Still Matters

You don’t need to be a programmer to appreciate Life. You don’t need to understand cellular automata or Turing machines. You just need to watch.

It’s a reminder that rules, even dumb rules, can create elegance.

It’s a sandbox for curiosity, stripped of distractions. No points. No sound. Just cause and effect, over and over.

And in an age of overstimulation, there’s something hauntingly pure about that.

When Patterns Whisper

In a way, Conway’s Game of Life is not about “life” at all. It’s about structure and fragility. Patterns appear strong, then crumble. Others seem weak but endure. Some generate endless novelty, while others freeze into silence.

It’s easy to project yourself into it — your own cycles, routines, reactions to your surroundings. The tension between stability and change. Between too much and too little.

It’s not storytelling in the traditional sense. But it feels like a story. One that writes itself fresh every time.

Conway’s Game of Life is still being explored, half a century after it first blinked into motion. It’s not a relic. It’s a living laboratory for rule-based wonder. And maybe that’s the strangest thing of all — that something so mechanical can still surprise us.

So open the grid. Place a few cells. Press play.

And let the silence think for you.

Discuss Conway’s Game of Life